If you were a wide-eyed follower of European football at the start of the 90s, you were soon made aware of Sampdoria.

Whether it was the sight of a smoking sailor in that beautiful blue shirt, a Cup Winners Cup win against Anderlecht in Stockholm, or when they went on to win Serie A in 1991.

Usurping Maradona’s Napoli as champions of Italy, while staving off the wealthy, big-game hunters from Milan, Turin, and Rome, was an astonishing achievement for a provincial side in the most competitive league in the world.

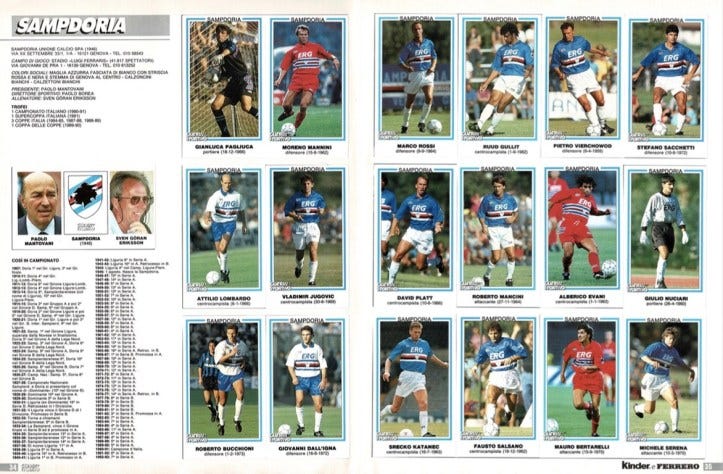

In 1992, coach Vujadin Boškov and his band of men came to London, only to lose narrowly to Johan Cruyff’s Barcelona in the European Cup Final. Roberto Mancini, Gianluca Vialli, Attilio Lombardo, Pietro Vierchowod and the melodically named Gianluca Pagliuca were names that most of us just came to know.

In the aftermath of the heartbreak from that May evening at Wembley, the weeks that followed saw notable departures. Boškov left for Roma, veteran midfielder Cerezo returned to Brazil and most notably, the emblematic Vialli left for Juventus.

While Vialli took his time to settle in Turin, Sampdoria most definitely took their time to adapt without Vialli. The 1992-1993 campaign was a disappointing one. England’s Des Walker struggled in his first and only season in Italy; and while Mancini and Lombardo were still performing to a high level, the port-city club lacked a focal point in attack. Sampdoria would end the season not even qualifying for European competition.

It was in this following season, coach Sven-Göran Eriksson’s second in charge, that serious inroads were made. Club owner Paolo Mantovani, popular with players and fans alike and “the best President I ever had” according to Eriksson, secured the services of David Platt from Juventus and Ruud Gullit and Alberigo Evani from Milan.

Both Platt and Gullit had points to prove from the previous year. Both were high-profile casualties of bloated squads and a three-foreigner rule that had restricted their playing time.

The new recruits immediately brought enthusiasm and a sense of purpose to their new team. Platt, then Gullit, scored on the opening day of the season to beat Napoli 2-1 at the San Paolo. Samp-a-doria as Don Howe used to call them, were now off and running.

Gullit, in particular, was a revelation throughout that Autumn. A former European Footballer of the Year, the Dutchman alongside his compatriot Marco Van Basten, German Lothar Matthäus, Michel Platini of France, and the Argentine Diego Maradona, are now part of that iconic band of “miti del calcio“.

These myths were star turns, raising the profile of Serie A, and all spearheading their teams to win league championships and European trophies.

Now adorned in that beautiful blue, the 33-year-old Gullit appeared just as he was at his peak in Milan. Too strong, too fast, and too deft for the world’s best defenders in the world’s most tactical league.

Platt too relished his new surroundings. Not only was he commanding a regular first-team place, but the England captain was also liberated by his new advanced role. He alongside Lombardo and the Serb Vladimir Jugović were all getting in on the act in a free-wheeling, free-scoring Sampdoria side.

Then came a bombshell. Mantovani, their owner and spiritual leader, passed away after a short illness on October 23, 1993. The benefactor and architect of Sampdoria’s ascent to the top. Mantovani, the man who brought in Trevor Francis, Liam Brady, Graeme Souness, Vierchowod, Cerezo, Mancini, Vialli, Boskov, Erikkson, Gullit, Platt and all the rest… had now gone.

The team rallied. The following day, Gullit was dominant in an impressive win away at Torino.

Then a week later on Halloween and on the day film director Federico Fellini died, Ruud was at it again in another matinee performance.

If Capello and Milan had doubted their former charge, he answered them emphatically, inspiring Samp to a 3-2 comeback win over the reigning champions.

As with most teams who earn the tag of entertainers, Sampdoria fell short at the other end of the pitch. Influential man-marker Marco Lanna who had left for Roma in the summer had not been effectively replaced. Neither did the team possess a defensive-minded midfielder since stalwart Fausto Pari had left the club some 18 months before.

Sampdoria had a glass jaw. There were home losses to Roma and Cagliari and a sub-par Inter blew them away at the San Siro just before Christmas.

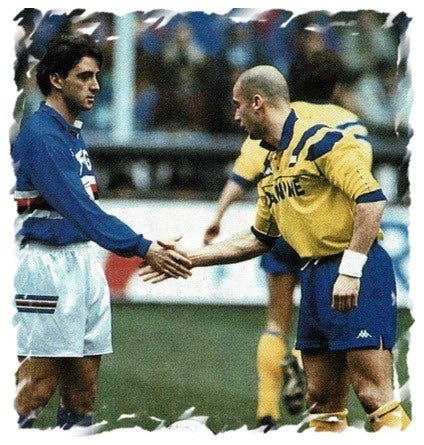

Indeed, of those teams in and around them, they could only draw with Parma and Juventus in Genoa and lost to both away from home. Sadly, if the opposition could contain Sampdoria’s attacking threat, frequently they would beat them.

Despite their vulnerability, by mid-March, they were in second place and chasing Milan. They were the only team to have beaten Capello’s men and now the two best sides in Italy would meet again at San Siro. These were the days of two points for a win and with eight rounds still to play, Milan was six points ahead and Sampdoria had to win.

After only ten seconds, Sampdoria broke the mythical Milan offside trap. Gullit, back at his old haunt, was released down the right-hand side and lofted a cross into an unmarked Roberto Mancini who had a clear path to the goal. He was no more than twelve yards out.

Rather than taking it on the volley, Mancini elected to control it on his thigh. By the time the ball dropped to his feet, Milan’s Alessandro Costacurta swooped in and made the block. It would be Sampdoria’s best opportunity in the game. Milan would go on to win the game, the Scudetto, and the European Cup.

The Mancini chance summed up the season. A moment that was microcosmic of the campaign in general. If Milan let the door open they would just as soon slam it shut before anyone could take advantage.

Eriksson’s men would find significant consolation in winning the Coppa Italia. Getting past Parma in the Semi-final before a comfortable 6-1 victory over Serie B Ancona in the two-legged final. In a fitting tribute to the memory of Paolo Mantovani, they were raising a trophy once more.

The Coppa Italia win was their last. The class of Sampdoria 1994 could be seen as the beginning of the end. At least at the end of a chapter. A chapter authored by Paolo Mantovani.

“I hate Sampdoria” just isn’t a sentence you hear much in football conversation. Like pub dogs or the sight of a Mini Cooper, everyone seems to have a soft spot for them.

Platt would later comment in his autobiography “With hindsight, had we believed in our chances of winning the championship a little more, we may well have succeeded.”

You can’t help but wonder just how much fun that would have been.